The quest for the ultimate weather-resistant doors

“We try everything we can to destroy these doors,” said Steen Frederichsen, European service manager for JELD-WEN’s sustainability initiatives in North Jutland, Denmark.

That’s not something you usually hear in the workplace. But in this case, Steen is just doing his job. He’s going above and beyond, in fact. In his former role, he was the project manager for STORM exterior doors and it was his responsibility to put those doors through the wringer.

His colleague, Health, Safety, Environment and Quality (HSEQ) Systems Manager Lennart Juhl is just as gleefully destructive.

“We give these doors our worst,” he said, smiling.

Lennart works on the production quality team and oversees processes and certifications.

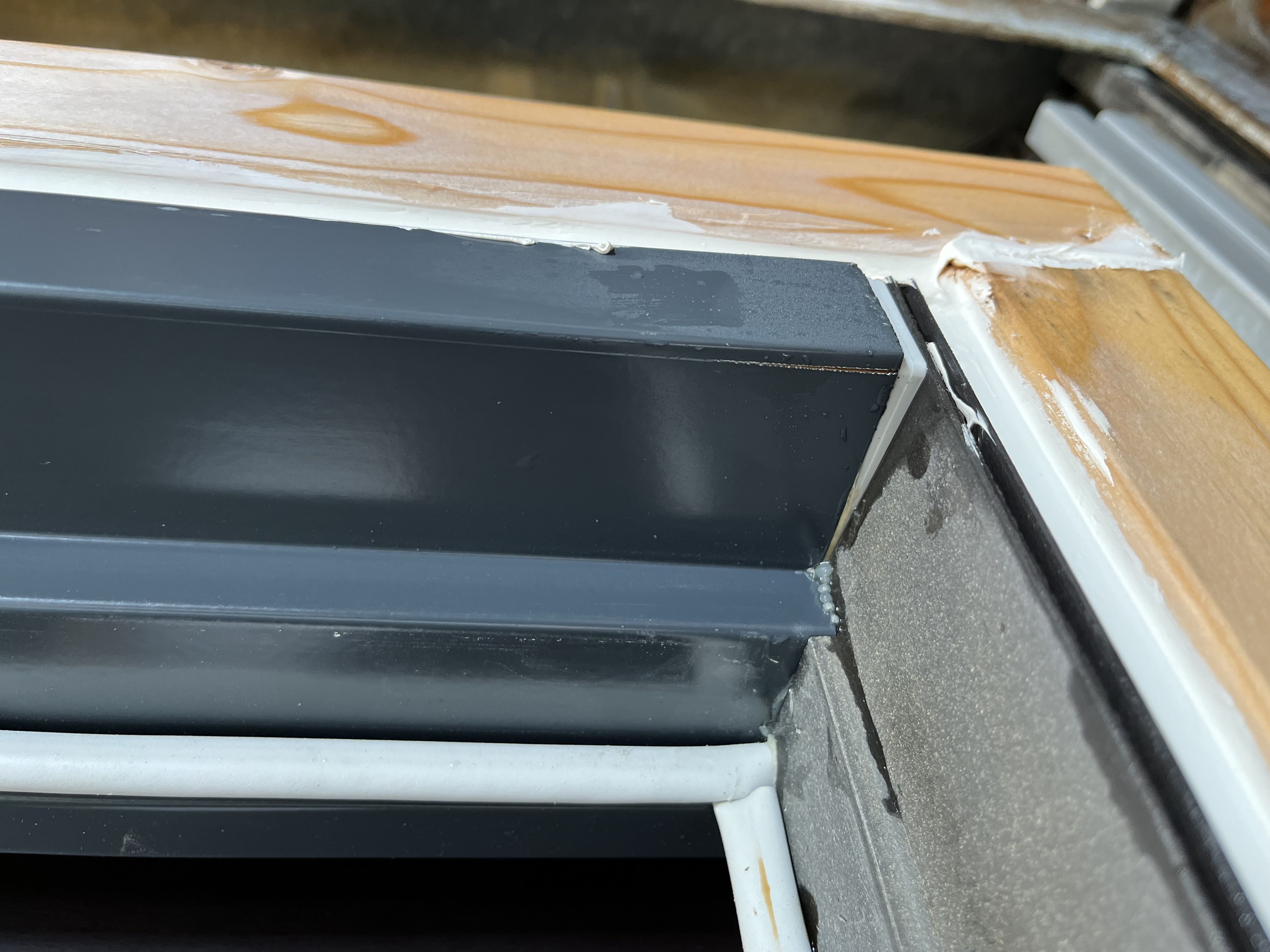

In early 2021, Lennart and Steen began an extensive testing protocol for a new generation of exterior doors. They wanted to see if the insulated doors could withstand extreme weather conditions such as those present on Norway’s west coast. At the same time, they tested standard exterior doors to have a basis for comparison. The pair went on their quest to find exterior doors under the JELD-WEN brand that could be reliable in weather conditions you’d experience worldwide and doors that can last for years to come. A high-pressure laminate (HPL) was the new material being put to the test. HPL is considered one of the most durable decorative surface materials and it’s available with special properties including chemical, fire and wear resistance.

A new design feature had also been added to this generation of STORM doors; grooves at the top of the door are intended to collect – and then blow away – excess water.

The team ran two sets of tests. One – performed inside a lab – was completed in two months. The other – performed outside in real-world conditions – required patience. They had to wait two years for those results.

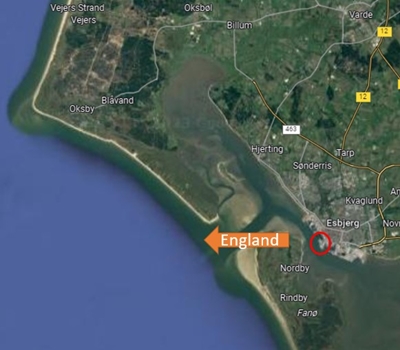

- Real world. Esbjerg, Denmark, a port town on the North Sea, has warm summers and mild winters. But the effects of the wind, sea and salty air can be brutal on the built environment. The wind speed can reach hurricane strength.

Steen’s team built five tiny 1.5 x 1.5-meter houses on the harbor to see how the STORM door performed, over time, when faced with whatever Mother Nature doled out. The tiny houses, which the team affectionately referred to as “Smurf houses,” were close enough to the surf that ocean waves could hit them. These houses were fully exposed to the harsh elements of the North Sea, including storms, sun, rain and salty air.

And salty air can do a lot of damage. Steen said, “If you were to drop your car in in the ocean, it would completely rust within 14 days.”

For a more comprehensive analysis, the team built five more tiny houses in a different location. These were constructed in a more protected environment behind the R&D lab in Åstorp, Sweden. Åstorp’s summers are typically pleasant, but its winters are long, often frigid, snowy and windy.

Steen said, “We wanted to understand how the same construction could behave differently in one environment compared to another environment in Scandinavia.” While no one inhabited the Smurf houses, they could have. All 10 were equipped with heating and ventilation systems that kept the interior at a constant 20 degrees Celsius (68 degrees Fahrenheit) to simulate a typical indoor climate.

- Lab. SINTEF, a research and testing lab in Trondheim, Norway, can simulate real-world conditions to conduct its testing. The team sent the lab a full-size exterior door to be placed into its rotating climate simulator for an accelerated climate test. The door was put in a carousel where it was exposed to 63-plus-degrees Celsius – simulating summer – and negative 20 degrees Celsius, an approximation of winter, as well as less extreme temperatures for spring and fall. The door got an hour of summer, an hour of spring and so on. It also got 30 liters of water dumped on it in an hour to simulate a rainstorm. It was rotated every hour for two months, which is the equivalent of spending 10 years in the real world.

In addition, the team had the lab perform an accelerated weather test on the new STORM door – the one with HPL coating – and a standard exterior door.

“This test allowed us to compare real-life results with lab-tested outcomes,” Steen said.

For the test in their backyard, members of Steen’s team checked the houses every three weeks. They measured the relative humidity inside to determine the door’s sturdiness. (That’s just one of many tests these doors undergo. At the R&D lab, they’re also opened and closed 200,000 times to see how they hold up.)

The data collected in Esbjerg was analyzed and compared with results from the reference houses in Sweden. The doors used in both locations were nearly identical since they were produced simultaneously and included new materials, such as HPL and a new frame construction covered with HPL to make it stronger. (The team is considering for the next generation of doors. (Even as one iteration of doors is going through testing, the quality team is already thinking about the next iteration.)

Lab conditions may have been harsh, but the real world turned out to be harsher. And still, the HPL doors did exactly what they were designed to do. They withstood the elements and kept the interior of the test homes dry and comfortable.

“We wanted to see how these doors performed in the winter, in the summer and during heavy rain,” Lennart said. His unemotional assessment: “The doors consistently performed as expected throughout the entire test period.”

Once the outside tests were complete – and the doors were deemed structurally sound and durable – the team still wasn’t satisfied. Engineers brought the doors inside, sliced them in half lengthwise and examined the interiors to determine if any damage was done to the core that wasn’t visible from the outside.

That’s right, one of the final stages in the process is basically a door dissection.

Steen and Lennart do not know of another division that has devised a gauntlet as thorough and punishing as theirs. While these weather-resistant doors will be sold only in Scandinavia, the technology and lessons learned will be shared company-wide.

The testing ended in June 2023, and already some of the findings have been put into practice. Small changes, including new and improved methods to install hardware, have been made to JELD-WEN’s basic exterior doors in Scandinavia.

Customers are the real beneficiaries of all this rigor.

“We believe our customers will greatly benefit from these extensive tests because we will offer them better and stronger construction which can withstand the extreme changes in weather conditions we see today,” Steen said.

To bring customers the very best, JELD-WEN engineers put their doors through the very worst.